Bilingual Education – Picking flowers with two hands

Let’s start at the end. On a vegetable patch of our memory lies “Akeelah and the Bee”. The film, released in 2006, is directed by Doug Atchison. Keke Palmer plays a teenager with the ingenuity to deconstruct words in this action-dissecting verb we call “spelling”. Carlita Cássimo, 12 years old and born in Ripele, a town in the district of Monapo – Nampula, had never heard of the film. But when we listen to her story, it’s the film she invokes, as if fiction were a river that always runs low on the porous frontier of reality.

Carlita is the main star of Ripele’s Primary School – she is a reading champion at her school; in the ZIP (Pedagogical Influence Zone – a group of schools in the same jurisdiction); and in the district. Let the provincial phase come. “I want to win,” she says in a thin voice, denouncing a shyness that one would not suspect when hearing her read. She reads Portuguese and Emakhuwa as quickly as Akeelah spelled. But until 2019, the year she entered the education system, she only spoke Emakhuwa.

School was a whole new world and she was apprehensive knowing that she would have to learn a language she didn’t know. The language itself is unfamiliar with the world she grew up trying to decipher. As luck would have it, she was part of the first group that was initiated to bilingual education in her school, as if to acknowledge the Portuguese language’s flaw in encompassing a culture that has always existed with its own codes. “I was happy to see that my teacher spoke Emakhuwa,” she says. And it was precisely Emakhuwa that helped her to learn and apprehend the world presented to her in Portuguese. This is the greatest generosity of a language, of any language: pointing out clues, opening paths, suggesting shortcuts, mapping connections and making it reach other languages. Even more so for a multilingual country like Mozambique, where it appears that around 80% of the population does not speak Portuguese as a native language. “There are areas where students only speak the native language and learning Portuguese can be much more complicated than learning maths,” says Suzana Agostinho Mendes, a teacher since 2013, in Alto-Molocué, Zambézia. “In monolingual teaching, teachers spoke practically only to themselves. If we wanted students to participate, we really needed to revert to native languages. Now, with the formalization of bilingual education, the approval rate has improved a lot,” she remarks.

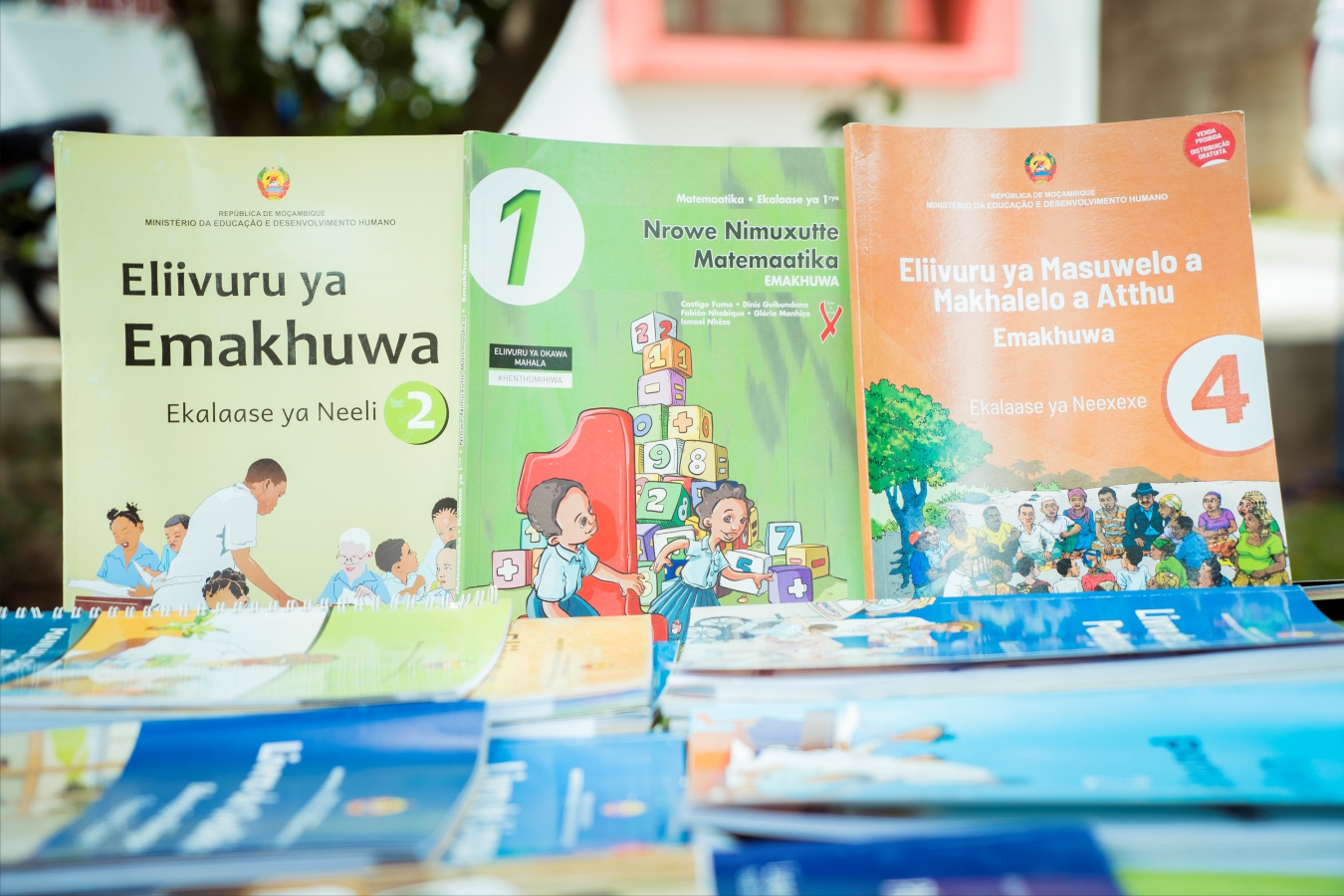

It’s support from programs like SABER, funded by USAID and implemented in Nampula, Zambézia, Cabo Delgado and Niassa, that is driving this system forward. The network includes more than 3000 schools, with particular emphasis on Zambézia and Nampula, with 739 and 1,039 schools covered. The books are translated into about 20 languages. In 2022 alone, more than 4 million books benefited more than one million students who, in their own language, take their first steps in this great marathon that is Education.

This feature was produced with support from USAID.

Edição 79 Maio/Junho| Download.

0 Comments