Wild roses

“Flowers don’t wait”

Isabel Tembe can distinguish the colour of roses with her eyes closed, just by feeling the scent: the softness of salmon, the sweetness of pink or the intensity of yellow. Her sensitivity and also her taste evolved over time. Over the years, she became better acquainted with the characteristics of each variety, and no two are alike. “In the beginning, I liked the red one the most because it was the most present on the market; but little by little I fell in love with the pink. You put it in the living room and, just passing by, you immediately feel that perfume.”

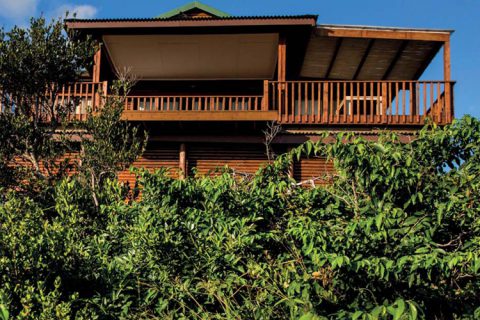

We are in the Mahotas neighbourhood, on the outskirts of Maputo, on a plot of two and a half hectares, where native trees grow vigorously as in a nature reserve. We penetrate the bush until we reach a clearing where we find rows of rose bushes of different colours, planted in black plastic bags (later they explain to us that planting in bags, instead of directly on the ground, makes water consumption for irrigation more efficient).

This is one of the few national productions of roses that Mozambique has and is the result of a long exercise in patience. Juan Estrada, Isabel’s partner, tells us the history of this adventure, as we walk among the plants. The first seed was sown 20 years ago, but it was only in 2010 that the production gained more importance. It was at that time that, together with their first partner, Francisco António Macaringue, they acquired three varieties of wild plants in a small rose garden at the Mozambican Institute of Agricultural Research, in Boane.

“Flowers don’t wait,” Juan Estrada says. Just like in life, in the face of obstacles and adversity, you have to move on.

“The rose gives life! Even if you’re in a bad mood, just smell that perfume and you’ll feel better right away!,” Isabel says.

The years that followed brought countless hurdles to test their resolve. The death of their partner, in 2013, led to the suspension of the project for more than a year. When, at the end of that period, they decided to relaunch the activity, Juan was incredulous: after clearing the land, he discovered that 300 plants had resisted. Perhaps that is why his dedication to the project is unshakable. They faced periods of drought, water crises, a fire that destroyed a large part of the production, but they refused to give up. If there’s one thing he’s learned over the years, it’s that “flowers don’t wait”. Just like in life, in the face of obstacles and adversity, you have to move on.

Today, Isabel and Juan have about 800 plants which generate an average of 80 to 100 flowers a day. The goal for this year is to reach 2000 grafted plants, of which about a quarter will be for gardens and the rest for sale in florists.

However, the biggest battle that Isabel and Juan are fighting is probably the very market that has accustomed consumers to the imported red rose. The strongest day in terms of marketing is easy to guess: Saint Valentine’s Day, celebrated on 14 February. On stalls or in postcard shops, the image of the fleshy red rose has become a cliché. But, as with industrially produced fruit – which can look perfect – you just have to feel it to realize that it has no aroma or taste.

But it’s not the masses that Isabel and Juan want to reach. They understand that the customer profile for their wild roses is niche: they prefer organic to industrial cultivation; the imperfection of the organic product to the perfection of mass production. And so, little by little, with a lot of persistence, they guarantee a constant flow of regular customers who receive an explosion of colour and aroma at home every week. “The rose gives life! Even if you’re in a bad mood, just smell that perfume and you’ll feel better right away, it seems to make you happy!,” Isabel says. And she adds: “Even after the flower dries, the petals still retain their scent. That’s why I always have roses at home in every corner – even in the bathroom!”

0 Comments