The drama of the pandemic in the informal sector

“Nothing can be so bad that it can’t get worse,” a popular saying goes. This is a reflection of what is currently seen in the various industries, especially in the informal sector, since the pandemic broke out. A sector that, long before the pandemic, had already suffered from several problems.

In the country, the informal sector has always been one of the areas of economic activity most penalized by the authorities due to the lack of organisation, but also because it is one of the businesses that disrupts order in urban centres. And, with the pandemic, the siege got tighter, many street sellers saw their business fail with the adoption of restrictive measures to contain the spread of the COVID-19 virus.

The impact was direct on informal sellers. Before the measures to contain the spread of COVID-19, the Municipality of Maputo had already launched a campaign to evacuate the streets and sidewalks of all economic activity developed there, which triggered the crisis among street sellers.

The informal business of selling coconut water and sugar cane juice was for many years the main source of family income for many young people who wandered almost always through the various arteries of the city of Maputo. However, the pandemic arrived and the business was swallowed up.

Although some are still working, there is a retraction in activity. “Everything is at a standstill, what I earn now is not enough, movement has fallen a lot,” Titos Albino considers, one of the sellers who continues to conduct business.

Currently, Titos Albino doesn’t work along the beach of Costa do Sol and Avenida 10 de Novembro, places that were the epicenter of this activity, since few people have gone to these places except those who practice their physical activities.

It is not just this business that has been affected by the pandemic. All informal activity has been stifled since March, a period in which the first state of emergency in the country was decreed.

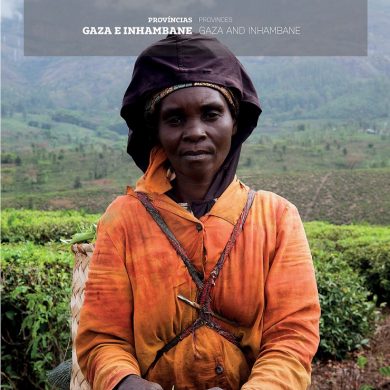

Marta Elias is a street vendor selling roasted peanuts and, since last year, she has not seen the business flowing as before the pandemic. “Now they don’t buy as much as they used to, but I also don’t go around much for fear of the pandemic. I prefer to stay in just one corner,” Marta tells us.

All informal activity has been stifled since March 2020, when the first state of emergency in the country was decreed.

Economists Aleia Rachide and João Mosca, in a study entitled Impact of COVID-19 on informal economic agents in the city of Maputo, note that there is an enormous sacrifice in exercising the activity by informal trade agents in markets, streets and sidewalks, as the flow of movement has also decreased slightly. As a consequence, “the loss of income was significant in the context of precautionary measures against the spread of the virus.”

“There is also a reduction in the effort of the people who carry out this activity, which is measured by the duration of the working day, which culminates in the reduction of the volume of sales and, consequently, of the net income,” the two economists point out.

About 11 million Mozambicans depend on informal activities for their livelihood.

In turn, the municipality considers that it doesn’t want to see people go hungry, however, “we want to prevent the spread of this virus and eliminate transmission in the community in which the city of Maputo is located.”

João Munguambe, councilor for the local economy in the municipality of Maputo, guaranteed that “our objective is that the population is safe and without the risk of being contaminated by COVID-19.”

According to data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), it is estimated that the formal economy generates 700,000 jobs, however, approximately 11 million people are forced to seek their livelihood in a variety of informal trade activities. Now with the pandemic, their future has become unknown.

Issue 66 Mar/Apr | Download

0 Comments